Before the Gregorian Reform the Latin Church at the Turn of the First Millennium Book Review

Christianity in the Middle Ages covers the history of Christianity from the Fall of the Western Roman Empire (c. 476). The end of the period is variously divers. Depending on the context, events such as the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Christopher Columbus's first voyage to the Americas in 1492, or the Protestant Reformation in 1517 are sometimes used.[1]

In Christianity's ancient Pentarchy, v patriarchies held special eminence: the sees of Rome, Constantinople, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria. The prestige of almost of these sees depended in part on their apostolic founders, or in the case of Byzantium/Constantinople, that information technology was the new seat of the continuing Eastern Roman, or Byzantine Empire. These bishops considered themselves the successors of those apostles.[2] In improver, all v cities were early centres of Christianity, they lost their importance after the Levant was conquered past the Sunni Caliphate.

Early Middle Ages (476–799) [edit]

Mosaic of Justinian I in the church building of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy

The Early Heart Ages commenced with the deposition of the last western Roman emperor in 476, to be followed past the barbarian king, Odoacer, to the coronation of Charlemagne every bit "Emperor of the Romans" by Pope Leo III in Rome on Christmas Solar day, 800. The year 476, however, is a rather artificial segmentation.[3] In the East, Roman imperial rule continued through the catamenia historians now call the Byzantine Empire. Even in the West, where imperial political control gradually declined, distinctly Roman culture continued long afterwards; thus historians today adopt to speak of a "transformation of the Roman world" rather than a "fall of the Roman Empire." The advent of the Early Middle Ages was a gradual and often localised procedure whereby, in the West, rural areas became ability centres whilst urban areas declined. With the Muslim invasions of the seventh century, the Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) areas of Christianity began to accept on distinctive shapes. Whereas in the E the Church maintained its strength, in the West the Bishops of Rome (i.eastward., the Popes) were forced to suit more apace and flexibly to drastically changing circumstances. In particular whereas the bishops of the Due east maintained clear allegiance to the Eastern Roman Emperor, the Bishop of Rome, while maintaining nominal allegiance to the Eastern Emperor, was forced to negotiate delicate balances with the "barbarian rulers" of the sometime Western provinces. Although the greater number of Christians remained in the Eastward, the developments in the West would set the phase for major developments in the Christian earth during the later centuries.[4]

Early Medieval Papacy [edit]

After the Italian peninsula fell into warfare and turmoil due to the barbarian tribes, the Emperor Justinian I attempted to reassert regal dominion in Italian republic from the East, against the Gothic aristocracy. The subsequent campaigns were more or less successful, and an Imperial Exarchate was established for Italia, only imperial influence was limited. The Lombards then invaded the weakened peninsula, and Rome was substantially left to fend for itself. The failure of the East to send assist resulted in the popes themselves feeding the city with grain from papal estates, negotiating treaties, paying protection coin to Lombard warlords, and, failing that, hiring soldiers to defend the city.[5] Eventually the popes turned to others for support, particularly the Franks.

Spread Beyond the Roman Empire [edit]

As the political boundaries of the Roman Empire diminished and then complanate in the Due west, Christianity spread beyond the old borders of the Empire and into lands that had never been under Rome.

Irish Missionaries [edit]

Get-go in the fifth century, a unique culture developed effectually the Irish gaelic Sea consisting of what today would be called Wales and Ireland. In this environment, Christianity spread from Roman United kingdom to Republic of ireland, especially aided by the missionary activity of St. Patrick with his first-order of 'patrician clergy', active missionary priests accompanying or following him, typically Britons or Irish ordained by him and his successors.[six] Patrick had been captured into slavery in Ireland and, post-obit his escape and later induction equally bishop, he returned to the isle that had enslaved him and then that he could bring them the Gospel. Presently, Irish gaelic missionaries such as Columba and Columbanus spread this Christianity, with its distinctively Irish features, to Scotland and the Continent. One such feature was the organization of private penitence, which replaced the one-time practice of penance as a public rite.[7]

Anglo-Saxons, English language [edit]

Although southern Uk had been a Roman province, in 407 the imperial legions left the isle, and the Roman elite followed. Some time later that century, diverse barbaric tribes went from raiding and pillaging the island to settling and invading. These tribes are referred to as the "Anglo-Saxons", predecessors of the English language. They were entirely pagan, having never been part of the Empire, and although they experienced Christian influence from the surrounding peoples, they were converted past the mission of St. Augustine sent by Pope Gregory the Great. The majority of the remaining British population converted from Christianity back to their Pagan roots. Contrary to popular belief, the conversion of Anglo-Saxons to Christianity was incredibly slow. The Anglo-Saxons had little interest in changing their organized religion and even initially looked downwardly upon Christianity due to conquering the Christian British people decades earlier. It took most a century to convert only the aristocracy of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity with many still converting dorsum to Paganism. After this, the common folk took a few hundred more years to convert to Christianity and their reasoning for converting was in big office due to the dignity.[8] Originally, Anglo-Saxon leaders claimed divine descent while taking function in many rituals and practices for Paganism but later on their conversion they in turn became spiritual leaders for Christianity in Great britain. Soon Anglo-Saxons started to incorporate their old Pagan stories and figures into Christianity, such as the Pagan god Woden condign sixteenth in descent from 'Sceaf, Noah'south son in the Bible.[9] Later, under Archbishop Theodore, the Anglo-Saxons enjoyed a golden age of culture and scholarship. Shortly, of import English missionaries such every bit SS. Wilfrid, Willibrord, Lullus and Boniface would begin evangelising their Saxon relatives in Germany.[x]

Franks [edit]

Saint Remigius baptises Clovis.

The largely Christian Gallo-Roman inhabitants of Gaul (mod French republic) were overrun by Germanic Franks in the early fifth century. The native inhabitants were persecuted until the Frankish King, Clovis I converted from paganism to Roman Catholicism in 496. Clovis insisted that his beau nobles follow suit, strengthening his newly established kingdom by uniting the religion of the rulers with that of the ruled.[10]

Frisians of the Low Countries [edit]

In 698, the Northumbrian Benedictine monk, Willibrord was commissioned past Pope Sergius I as bishop of the Frisians in what is now the netherlands. Willibrord established a church in Utrecht.

Much of Willibrord's work was wiped out when the pagan Radbod, rex of the Frisians destroyed many Christian centres betwixt 716 and 719. In 717, the English missionary Boniface was sent to help Willibrord, re-establishing churches in Frisia and continuing to preach throughout the pagan lands of Germany. Boniface was killed by pagans in 754.

Iconoclasm [edit]

Iconoclasm as a move began within the Eastern Christian Byzantine church in the early eighth century, following a series of heavy military reverses confronting the Muslims. There was a Christian move in the 8th and 9th centuries against the worship of imagery, acquired past worry that the art might be idolatrous.[4] Sometime between 726 and 730 the Byzantine Emperor Leo 3 the Isaurian ordered the removal of an image of Jesus prominently placed over the Chalke gate, the ceremonial entrance to the Corking Palace of Constantinople, and its replacement with a cantankerous. This was followed by orders banning the pictorial representation of the family unit of Christ, subsequent Christian saints, and biblical scenes. In the W, Pope Gregory III held ii synods at Rome and condemned Leo's actions. In Leo'due south realms, the Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754 ruled that the culture of holy portraits (see icon) was non of a Christian origin and therefore heretical.[11] The movement destroyed much of the Christian church building's early artistic history, to the bully loss of subsequent art and religious historians. The iconoclastic movement itself was later defined every bit heretical in 787 under the 7th Ecumenical council, but enjoyed a cursory resurgence between 815 and 842.

High Middle Ages (800–1300) [edit]

Carolingian Renaissance [edit]

The Carolingian Renaissance was a period of intellectual and cultural revival during the late eighth century and ninth century, more often than not during the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. There was an increase of literature, the arts, architecture, jurisprudence, liturgical and scriptural studies. The period also saw the development of Carolingian minuscule, the ancestor of modern lower-example script, and the standardisation of Latin which had hitherto become varied and irregular (see Medieval Latin). To address the problems of illiteracy amidst clergy and court scribes, Charlemagne founded schools and attracted the most learned men from all of Europe to his courtroom, such equally Theodulf, Paul the Deacon, Angilbert, Paulinus of Aquileia.

Growing tensions between Due east and W [edit]

The cracks and fissures in Christian unity which led to the E-West Schism started to get evident as early every bit the fourth century. Cultural, political, and linguistic differences were often mixed with the theological, leading to schism.

The transfer of the Roman capital to Constantinople inevitably brought mistrust, rivalry, and even jealousy to the relations of the 2 smashing sees, Rome and Constantinople. It was easy for Rome to exist jealous of Constantinople at a time when it was rapidly losing its political prominence. Estrangement was also helped along by the German language invasions in the West, which effectively weakened contacts. The ascension of Islam with its conquest of most of the Mediterranean coastline (not to mention the arrival of the pagan Slavs in the Balkans at the same time) further intensified this separation by driving a concrete wedge between the two worlds. The once homogenous unified world of the Mediterranean was fast vanishing. Advice betwixt the Greek East and Latin Due west past the 600s had get dangerous and practically ceased.[12]

Two basic problems – the nature of the primacy of the bishop of Rome and the theological implications of calculation a clause to the Nicene Creed, known as the filioque clause – were involved. These doctrinal bug were first openly discussed in Photius's patriarchate.

By the 5th century, Christendom was divided into a pentarchy of 5 sees with Rome accorded a primacy. The 4 Eastern sees of the pentarchy, considered this determined by canonical decision and did not entail hegemony of any one local church or patriarchate over the others. Nonetheless, Rome began to interpret her primacy in terms of sovereignty, as a God-given right involving universal jurisdiction in the Church. The collegial and conciliar nature of the Church building, in consequence, was gradually abandoned in favour of supremacy of unlimited papal power over the unabridged Church building. These ideas were finally given systematic expression in the West during the Gregorian Reform motion of the eleventh century. The Eastern churches viewed Rome's understanding of the nature of episcopal power as being in direct opposition to the Church's substantially conciliar structure and thus saw the two ecclesiologies every bit mutually antithetical. For them, specifically, Simon Peter'southward primacy could never be the sectional prerogative of any one bishop. All bishops must, similar St. Peter, confess Jesus equally the Christ and, every bit such, all are Peter's successors. The churches of the East gave the Roman See, primacy but not supremacy. The Pope being the first among equals, but non infallible and non with absolute authority.[13]

The other major irritant to Eastern Christendom was the Western use of the filioque clause—pregnant "and the Son"—in the Nicene Creed . This likewise developed gradually and entered the Creed over time. The effect was the addition past the West of the Latin clause filioque to the Creed, every bit in "the Holy Spirit... who gain from the Begetter and the Son," where the original Creed, sanctioned past the councils and still used today, by the Eastern Orthodox simply states "the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of Life, who gain from the Male parent." The Eastern Church argued that the phrase had been added unilaterally and, therefore, illegitimately, since the Eastward had never been consulted.[fourteen] In the final analysis, just another ecumenical council could introduce such an amending. Indeed, the councils, which drew up the original Creed, had expressly forbidden any subtraction or add-on to the text. In addition to this ecclesiological outcome, the Eastern Church also considered the filioque clause unacceptable on dogmatic grounds. Theologically, the Latin interpolation was unacceptable since it implied that the Spirit now had two sources of origin and procession, the Father and the Son, rather than the Father alone.[15]

Photian Schism [edit]

In the 9th century Advertizing, a controversy arose betwixt Eastern (Byzantine, later Orthodox) and Western (Latin, later Roman Catholic) Christianity that was precipitated by the opposition of the Roman Pope John VIII to the appointment by the Byzantine emperor Michael Three of Photius I to the position of patriarch of Constantinople. Photios was refused an apology by the pope for previous points of dispute betwixt the East and West. Photius refused to accept the supremacy of the pope in Eastern matters or accept the filioque clause. The Latin delegation at the council of his consecration pressed him to accept the clause in order to secure their support.

The controversy as well involved Eastern and Western ecclesiastical jurisdictional rights in the Bulgarian church, as well as a doctrinal dispute over the Filioque ("and from the Son") clause. That had been added to the Nicene Creed by the Latin church, which was afterwards the theological breaking point in the ultimate Great E-West Schism in the eleventh century.

Photius did provide concession on the issue of jurisdictional rights concerning Bulgaria and the papal legates made do with his render of Bulgaria to Rome. This concession, even so, was purely nominal, as Bulgaria's return to the Byzantine rite in 870 had already secured for information technology an autocephalous church. Without the consent of Boris I of Republic of bulgaria, the papacy was unable to enforce any of its claims.

East-West Schism [edit]

The Due east-West Schism, or Slap-up Schism, separated the Church into Western (Latin) and Eastern (Greek) branches, i.e., Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. It was the beginning major division since certain groups in the E rejected the decrees of the Council of Chalcedon (see Oriental Orthodoxy), and was far more than significant. Though normally dated to 1054, the East-W Schism was actually the consequence of an extended period of estrangement between Latin and Greek Christendom over the nature of papal primacy and sure doctrinal matters similar the filioque, but intensified by cultural and linguistic differences.

The "official" schism in 1054 was the excommunication of Patriarch Michael Cerularius of Constantinople, followed by his excommunication of papal legates. Attempts at reconciliation were made in 1274 (by the Second Quango of Lyon) and in 1439 (by the Quango of Basel), simply in each case the eastern hierarchs who consented to the unions were repudiated past the Orthodox as a whole, though reconciliation was achieved between the West and what are now called the "Eastern Rite Catholic Churches." More recently, in 1965 the mutual excommunications were rescinded by the Pope and the Patriarch of Constantinople, though schism remains.

Both groups are descended from the Early Church, both admit the apostolic succession of each other's bishops, and the validity of each other's sacraments. Though both admit the primacy of the Bishop of Rome, Eastern Orthodoxy understands this as a primacy of honour with express or no ecclesiastical authority in other dioceses.

The Orthodox East perceived the Papacy as taking on monarchical characteristics that were not in line with the church's traditional human relationship with the emperor.

The final breach is often considered to have arisen after the capture and sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. Crusades confronting Christians in the East past Roman Catholic crusaders was not exclusive to the Mediterranean though (see also the Northern Crusades and the Boxing of the Ice). The sacking of Constantinople, especially the Church of Holy Wisdom and the Church of the Holy Apostles, and institution of the Latin Empire every bit a seeming try to supersede the Orthodox Byzantine Empire in 1204 is viewed with some rancour to the present twenty-four hour period. Many in the Eastward saw the deportment of the West as a prime number determining factor in the weakening of Byzantium. This led to the Empire'due south eventual conquest and fall to Islam. In 2004, Pope John Paul II extended a formal amends for the sacking of Constantinople in 1204; the apology was formally accepted by Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople. Many things that were stolen during this time: holy relics, riches, and many other items, are still held in various Western European cities, particularly Venice.

Monastic Reform [edit]

A view of the Abbey of Cluny.

Cluny [edit]

From the sixth century onward nearly of the monasteries in the Westward were of the Benedictine Society. Owing to the stricter adherence to a reformed Benedictine rule, the abbey of Cluny became the acknowledged leader of western monasticism from the subsequently 10th century. Cluny created a large, federated order in which the administrators of subsidiary houses served as deputies of the abbot of Cluny and answered to him. The Cluniac spirit was a revitalising influence on the Norman church, at its acme from the second half of the 10th centuries through the early on 12th.

Cîteaux [edit]

The side by side wave of monastic reform came with the Cistercian Movement. The first Cistercian abbey was founded in 1098, at Cîteaux Abbey. The keynote of Cistercian life was a render to a literal observance of the Benedictine rule, rejecting the developments of the Benedictines. The most striking feature in the reform was the render to manual labour, and specially to field-work. Inspired by Bernard of Clairvaux, the chief builder of the Cistercians, they became the principal force of technological diffusion in medieval Europe. By the end of the twelfth century the Cistercian houses numbered 500, and at its peak in the 15th century the order claimed to take close to 750 houses. Most of these were built in wilderness areas, and played a major part in bringing such isolated parts of Europe into economical cultivation.

Mendicant Orders [edit]

A tertiary level of monastic reform was provided by the establishment of the Mendicant orders. Commonly known every bit friars, mendicants live nether a monastic dominion with traditional vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, but they emphasise preaching, missionary activity, and education, in a secluded monastery. Beginning in the 12th century, the Franciscan order was instituted past the followers of Francis of Assisi, and thereafter the Dominican Order was begun by St. Dominic.

Investiture Controversy [edit]

Henry IV at the gate of Canossa, by August von Heyden

The Investiture Controversy, or Lay investiture controversy, was the most pregnant conflict between secular and religious powers in medieval Europe. It began every bit a dispute in the 11th century betwixt the Holy Roman Emperor Henry Four, and Pope Gregory Seven concerning who would appoint bishops (investiture). The end of lay investiture threatened to undercut the power of the Empire and the ambitions of noblemen for the benefit of Church building reform.

Bishops collected revenues from estates attached to their bishopric. Noblemen who held lands (fiefdoms) hereditarily passed those lands on within their family. Nevertheless, because bishops had no legitimate children, when a bishop died it was the rex's correct to appoint a successor. So, while a rex had piddling recourse in preventing noblemen from acquiring powerful domains via inheritance and dynastic marriages, a king could keep careful command of lands nether the domain of his bishops. Kings would bestow bishoprics to members of noble families whose friendship he wished to secure. Furthermore, if a king left a bishopric vacant, then he collected the estates' revenues until a bishop was appointed, when in theory he was to repay the earnings. The infrequence of this repayment was an obvious source of dispute. The Church wanted to terminate this lay investiture because of the potential abuse, not merely from vacant sees but besides from other practices such equally simony. Thus, the Investiture Competition was part of the Church'southward attempt to reform the episcopate and provide better pastoral care.

Pope Gregory 7 issued the Dictatus Papae, which declared that the pope alone could appoint or depose bishops, or translate them to other sees. Henry IV's rejection of the prescript lead to his excommunication and a ducal defection; eventually Henry received absolution after dramatic public penance barefoot in Alpine snow and cloaked in a hairshirt (meet Walk to Canossa), though the revolt and conflict of investiture connected. Likewise, a like controversy occurred in England between Rex Henry I and St. Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, over investiture and ecclesiastical revenues nerveless by the king during an episcopal vacancy. The English dispute was resolved by the Concordat of London, 1107, where the king renounced his claim to invest bishops just continued to crave an oath of fealty from them upon their election. This was a partial model for the Concordat of Worms (Pactum Calixtinum), which resolved the Imperial investiture controversy with a compromise that allowed secular authorities some mensurate of control simply granted the selection of bishops to their cathedral canons. As a symbol of the compromise, lay authorities invested bishops with their secular dominance symbolised by the lance, and ecclesiastical authorities invested bishops with their spiritual authority symbolised by the ring and the staff.

Crusades [edit]

The Crusades were a series of military machine conflicts conducted by Christian knights for the defence of Christians and for the expansion of Christian domains. Generally, the Crusades refer to the campaigns in the Holy Land sponsored by the papacy against invading Muslim forces. There were other crusades against Islamic forces in southern Kingdom of spain, southern Italy, and Sicily, as well as the campaigns of Teutonic knights against pagan strongholds in Eastern Europe (run across Northern Crusades). A few crusades such as the 4th Crusade were waged within Christendom against groups that were considered heretical and schismatic (also run into the Battle of the Ice and the Albigensian Crusade).

The Holy State had been office of the Roman Empire, and thus Byzantine Empire, until the Islamic conquests of the 7th and eighth centuries. Thereafter, Christians had generally been permitted to visit the sacred places in the Holy Land until 1071, when the Seljuk Turks closed Christian pilgrimages and assailed the Byzantines, defeating them at the Battle of Manzikert. Emperor Alexius I asked for help from Pope Urban II (1088–1099) for assistance against Islamic assailment. Urban Ii chosen upon the knights of Christendom in a speech communication made at the Council of Clermont on 27 November 1095, combining the idea of pilgrimage to the Holy State with that of waging a holy war against the invading forces.

In the First Crusade, subsequently 9 months of state of war of attrition, a traitor named Firuz led the Franks into the city of Antioch in 1098. Even so, after less than a calendar week, the might of an army numbering hundreds of thousands led by Kerbogah arrived and besieged the city. The crusaders reportedly had but 30,000 men and the Turks outnumbered them three to one; facing desertion and starvation, Bohemond was officially chosen to lead the crusader ground forces in June 1098. On the forenoon of 28 June, the crusader regular army, consisting of more often than not dismounted knights and foot soldiers because most horses had died at that point, sallied out to assail the Turks, and broke the line of Kerbogah'southward army, allowing the crusaders to gain complete command of the Antioch and its environs.[sixteen] The 2nd Crusade occurred in 1145 when Edessa was retaken by Islamic forces. Jerusalem would be held until 1187 and the Third Crusade, famous for the battles between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The Fourth Crusade, begun past Innocent Iii in 1202, intended to retake the Holy Country but was presently subverted by Venetians who used the forces to sack the Christian city of Zara. Innocent excommunicated the Venetians and crusaders.[ citation needed ] Eventually the crusaders arrived in Constantinople, but due to strife which arose betwixt them and the Byzantines,[ citation needed ] the crusaders sacked Constantinople and other parts of Asia Pocket-size, rather than proceeding to the Holy Land, finer establishing the Latin Empire of Constantinople in Greece and Asia Small-scale. This was effectively the last crusade sponsored by the papacy; later crusades were sponsored by individuals. Thus, though Jerusalem was held for nearly a century and other strongholds in the Near East would remain in Christian possession much longer, the crusades in the Holy Land ultimately failed to found permanent Christian kingdoms. The Europeans' defeat can in no small part be attributed to the excellent martial prowess of the Mameluke and Turks, who both utilized agile mounted archers in open battle and Greek fire in siege defense. However, ultimately it was the inability of the Crusader leaders to command coherently that doomed the military campaign. In addition, the failure of the missionaries to convert the Mongols to Christianity thwarted the hope for a Tartar- Frank alliance. The Mongols afterwards on converted to Islam.[17] Islamic expansion into Europe would renew and remain a threat for centuries, culminating in the campaigns of Suleiman the Magnificent in the sixteenth century. On the other hand, the crusades in southern Spain, southern Italy, and Sicily eventually led to the demise of Islamic ability in the regions; the Teutonic knights expanded Christian domains in Eastern Europe, and the much less frequent crusades within Christendom, such every bit the Albigensian Cause, accomplished their goal of maintaining doctrinal unity.[18]

Medieval inquisition [edit]

The Medieval Inquisition officially started in 1231, when Pope Gregory Ix appointed the first inquisitors to serve as papal agents to remove heresy. Heretics were seen as a menace to the Church and the showtime group dealt with by the inquisitors were the Cathars of southern France. The main tool used by the inquisitors was interrogation that oftentimes featured the utilize of torture followed past having heretics burned at the stake. After about a century this first medieval inquisition came to a conclusion. A new inquisition called the Spanish Inquisition was created by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in order to consolidate their dominion. This new inquisition was separated from the Roman Church building and the inquisition that came before it. At first it was primarily directed at Jews who converted to Christianity because many were suspicious that they did not actually catechumen to Christianity. Later it spread to targeting Muslims and the diverse peoples of the Americas and Asia.[19] The inquisitions in combination with the Albigensian Crusade were fairly successful in suppressing heresy.

Rise of universities [edit]

Modern western universities have their origins direct in the Medieval Church. They began every bit cathedral schools, and all students were considered clerics. This was a benefit equally it placed the students under ecclesiastical jurisdiction and thus imparted certain legal immunities and protections. The cathedral schools eventually became partially discrete from the cathedrals and formed their own institutions, the primeval being the University of Paris (c. 1150), the University of Bologna (1088), and the University of Oxford (1096).

Spread of Christianity [edit]

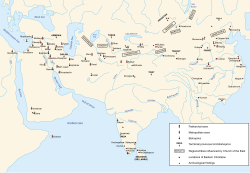

[edit]

Early on evangelisation in Scandinavia was begun by Ansgar, Archbishop of Bremen, "Apostle of the North". Ansgar, a native of Amiens, was sent with a grouping of monks to Jutland Denmark in around 820 at the time of the pro-Christian Jutish king Harald Klak. The mission was merely partially successful, and Ansgar returned two years later to Germany, after Harald had been driven out of his kingdom. In 829 Ansgar went to Birka on Lake Mälaren, Sweden, with his aide friar Witmar, and a small-scale congregation was formed in 831 which included the king's own steward Hergeir. Conversion was tiresome, nevertheless, and virtually Scandinavian lands were just completely Christianised at the time of rulers such as Saint Canute IV of Kingdom of denmark and Olaf I of Norway in the years post-obit AD 1000.

Stavronikita monastery, South-East view

Conversion of East and Southward Slavs [edit]

Though past 800 Western Europe was ruled entirely by Christian kings, Eastern Europe remained an area of missionary activity. For example, in the 9th century SS. Cyril and Methodius had all-encompassing missionary success in Eastern Europe among the Slavic peoples, translating the Bible and liturgy into Slavonic. The Baptism of Kiev in the 988 spread Christianity throughout Kievan Rus', establishing Christianity among the Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, Christianity made great inroads into Eastern Europe, including Kievan Rus'. The evangelisation, or Christianisation, of the Slavs was initiated by i of Byzantium'south most learned churchmen – the Patriarch Photius. The Byzantine emperor Michael 3 chose Cyril and Methodius in response to a request from Rastislav, the male monarch of Moravia who wanted missionaries that could minister to the Moravians in their own language. The 2 brothers spoke the local Slavonic vernacular and translated the Bible and many of the prayer books. As the translations prepared by them were copied by speakers of other dialects, the hybrid literary language Old Church Slavonic was created.

Methodius later went on to catechumen the Serbs.[20] Some of the disciples returned to Bulgaria where they were welcomed by the Bulgarian Tsar Boris I who viewed the Slavonic liturgy every bit a way to counteract Greek influence in the country. In a curt time the disciples of Cyril and Methodius managed to set and instruct the futurity Slavic clergy into the Glagolitic alphabet and the biblical texts. Methodius and Cyril were mainly living and working in the Macedonian urban center of Ohrid, which they made the religious capital of the Balkans.[ citation needed ]

Bulgaria was officially recognised as a patriarchate by Constantinople in 945, Serbia in 1346, and Russia in 1589. All these nations, still, had been converted long before these dates.

The missionaries to the Eastward and South Slavs had great success in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin every bit the Roman priests did, or Greek.

Mission to Great Moravia [edit]

When king Rastislav of Moravia asked Byzantium for teachers who could minister to the Moravians in their own language, Byzantine emperor Michael 3 chose 2 brothers, Cyril and Methodius. As their mother was a Slav from the hinterlands of Thessaloniki, the two brothers had been raised speaking the local Slavonic vernacular. Once commissioned, they immediately prepare about creating an alphabet, the Cyrillic script; they then translated the Scripture and the liturgy into Slavonic. This Slavic dialect became the basis of Sometime Church Slavonic which later evolved into Church Slavonic which is the mutual liturgical language still used by the Russian Orthodox Church building and other Slavic Orthodox Christians. The missionaries to the E and South Slavs had great success in part because they used the people's native language rather than Latin or Greek. In Slap-up Moravia, Constantine and Methodius encountered Frankish missionaries from Deutschland, representing the western or Latin co-operative of the Church, and more particularly representing the Holy Roman Empire as founded by Charlemagne, and committed to linguistic, and cultural uniformity. They insisted on the use of the Latin liturgy, and they regarded Moravia and the Slavic peoples as part of their rightful mission field.

When friction developed, the brothers, unwilling to exist a cause of dissension among Christians, travelled to Rome to see the Pope, seeking an agreement that would avoid quarrelling betwixt missionaries in the field. Constantine entered a monastery in Rome, taking the proper name Cyril, by which he is now remembered. However, he died just a few weeks thereafter.

Pope Adrian II gave Methodius the title of Archbishop of Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia) and sent him back in 869, with jurisdiction over all of Moravia and Pannonia, and authorisation to employ the Slavonic Liturgy. Shortly, however, Prince Ratislav, who had originally invited the brothers to Moravia, died, and his successor did not support Methodius. In 870 the Frankish king Louis and his bishops deposed Methodius at a synod at Ratisbon, and imprisoned him for a lilliputian over two years. Pope John VIII secured his release, but instructed him to terminate using the Slavonic Liturgy.

In 878, Methodius was summoned to Rome on charges of heresy and using Slavonic. This fourth dimension Pope John was convinced by the arguments that Methodius made in his defence and sent him back cleared of all charges, and with permission to utilise Slavonic. The Carolingian bishop who succeeded him, Witching, suppressed the Slavonic Liturgy and forced the followers of Methodius into exile. Many found refuge with King Boris of Bulgaria (852–889), under whom they reorganised a Slavic-speaking Church building. Meanwhile, Pope John'southward successors adopted a Latin-only policy which lasted for centuries.

Conversion of the Serbs and Bulgarians [edit]

Methodius subsequently went on to convert the Serbs. Some of the disciples, namely St. Kliment, St. Naum who were of noble Bulgarian descent and St. Angelaruis, returned to Bulgaria where they were welcomed by the Bulgarian Tsar Boris I who viewed the Slavonic liturgy as a way to annul Greek influence in the country. Prior to Christianity, the majority of Bulgaria was Pagan. In 876, Tsar Boris I adopted Christianity from Constantinople, making information technology the official religion of Bulgaria. Shortly after, Boris I accustomed many Christian missionaries into the country. At the time, the majority of the missionaries were Byzantines and Bulgarians. The conversion of Republic of bulgaria was particularly painful and bloody as many people were converted through force. However, many connected to secretly worship their pagan gods. Constantinople and Rome contended to attract the powerful Bulgaria through the apply of religion. After the carve up of the Eastern and Western churches in the 11th century, the Eastern church located in Constantinople took control of Bulgaria implementing Orthodox Christianity. Starting in the 14th century, the Ottomans conquered many places in the Balkans including Bulgaria, which led to many new forced and voluntary converts to Islam. Despite the constant warfare, the Christians and Muslims lived together in relative peace in Bulgaria. The two religious groups influenced each other'southward cultures and religious practices.[21] [22] In a brusk time the disciples of Cyril and Methodius managed to prepare and instruct the future Slav Bulgarian clergy into the Glagolitic alphabet and the biblical texts and in Advert 893, Bulgaria expelled its Greek clergy and proclaimed the Slavonic linguistic communication as the official language of the church building and the state.

Conversion of the Rus' [edit]

The success of the conversion of the Bulgarians facilitated the conversion of other East Slavic peoples, most notably the Rus', predecessors of Belarusians, Russians, and Ukrainians, as well as Rusyns. By the beginning of the eleventh century most of the pagan Slavic globe, including Russia, Bulgaria and Serbia, had been converted to Byzantine Christianity.

The traditional event associated with the conversion of Russia is the baptism of Vladimir of Kiev in 988, on which occasion he was too married to the Byzantine princess Anna, the sister of the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. However, Christianity is documented to take predated this result in the city of Kiev and in Georgia.

Today the Russian Orthodox Church building is the largest of the Orthodox Churches.

Late Middle Ages (1300–1499) [edit]

Hesychast Controversy [edit]

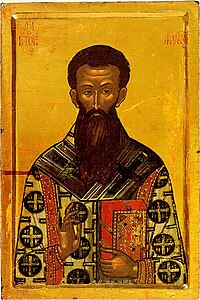

- Barlaam of Calabria

About the year 1337 Hesychasm attracted the attention of a learned member of the Orthodox Church, Barlaam of Calabria who at that time held the office of abbot in the Monastery of St Saviour's in Constantinople and who visited Mount Athos. Mount Athos was and then at the height of its fame and influence under the reign of Andronicus Three Palaeologus and under the 'first-ship' of the Protos Symeon. On Mountain Athos, Barlaam encountered Hesychasts and heard descriptions of their practices, also reading the writings of the teacher in Hesychasm of St Gregory Palamas, himself an Athonite monk. Trained in Western Scholastic theology, Barlaam was scandalised by Hesychasm and began to combat it both orally and in his writings. Equally a private teacher of theology in the Western Scholastic mode, Barlaam propounded a more intellectual and propositional approach to the knowledge of God than the Hesychasts taught. Hesychasm is a class of constant purposeful prayer or experiential prayer, explicitly referred to as contemplation. Descriptions of the Hesychast practices can exist found in the Philokalia, The Way of a Pilgrim, and St. John Climacus' The Ladder of Divine Ascent.

Barlaam took exception to, as heretical and blasphemous, the doctrine entertained by the Hesychasts as to the nature of the uncreated low-cal, the experience of which was said to be the goal of Hesychast practice. It was maintained by the Hesychasts to be of divine origin and to be identical to that light which had been manifested to Jesus' disciples on Mountain Tabor at the Transfiguration. This Barlaam held to be polytheistic, inasmuch equally information technology postulated ii eternal substances, a visible and an invisible God.

- Gregory Palamas

On the Hesychast side, the controversy was taken upwards past St Gregory Palamas, afterwards Archbishop of Thessalonica, who was asked by his boyfriend monks on Mt Athos to defend Hesychasm from the attacks of Barlaam. St Gregory himself, was well-educated in Greek philosophy. St Gregory dedicated Hesychasm in the 1340s at 3 dissimilar synods in Constantinople, and he also wrote a number of works in its defence.

In these works, St Gregory Palamas uses a distinction, already establish in the 4th century in the works of the Cappadocian Fathers, between the energies or operations (Gr. energies) of God and the essence (ousia) of God (see the Essence-Energies stardom). St Gregory taught that the energies or operations of God were uncreated. He taught that the essence of God tin can never be known by his creations even in the next life, only that his uncreated energies or operations can be known both in this life and in the adjacent, and convey to the Hesychast in this life and to the righteous in the next life a true spiritual knowledge of God (see theoria). In Palamite theology, it is the uncreated energies of God that illumine the Hesychast who has been vouchsafed an experience of the Uncreated Calorie-free. Palamas referred to this experience as an apodictic (see Aristotle) validation of God rather than a scholastic contemplative or dialectical validation of God.

- Synods

In 1341 the dispute came before a synod held at Constantinople and was presided over by the Emperor Andronicus; the synod, taking into account the regard in which the writings of the pseudo-Dionysius were held, condemned Barlaam, who recanted and returned to Calabria, later becoming a bishop in the Roman Catholic Church.

One of Barlaam'south friends, Gregory Akindynos, who originally was also a close friend of St Gregory Palamas, took upward the controversy, and three other synods on the subject were held, at the second of which the followers of Barlaam gained a cursory victory. But in 1351 at a synod under the presidency of the Emperor John VI Cantacuzenus, Hesychast doctrine was established every bit the doctrine of the Orthodox Church.

- Aftermath

Up to this twenty-four hour period, the Roman Catholic Church has never fully accustomed Hesychasm, particularly the distinction between the energies or operations of God and the essence of God, and the notion that those energies or operations of God are uncreated. In Roman Cosmic theology equally it has developed since the Scholastic period c. 1100–1500, the essence of God can be known, only only in the adjacent life; the grace of God is e'er created; and the essence of God is pure act, and so that there can be no stardom between the energies or operations and the essence of God (see, eastward.thou., the Summa Theologiae of St Thomas Aquinas). Some of these positions depend on Aristotelian metaphysics.

- Views of mod historians

The contemporary historians Cantacuzenus and Nicephorus Gregoras deal very copiously with this subject, taking the Hesychast and Barlaamite sides respectively. Respected fathers of the church have held that these councils that concord that experiential prayer is Orthodox, refer to these every bit councils as Ecumenical Councils 8 and Nine. Begetter John S. Romanides, Hierotheos (Vlachos) of Nafpaktos, and the Very Rev. Prof. Dr. George Metallinos, Professor of theology at Athens Greece (see gnosiology).

Avignon Papacy (1309-1378) and Western Schism (1378-1417) [edit]

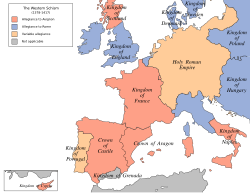

Map showing support for Avignon (crimson) and Rome (blueish) during the Western Schism

The Western Schism, or Papal Schism, was a prolonged catamenia of crisis in Latin Christendom from 1378 to 1416, when there were two or more claimants to the See of Rome and there was conflict concerning the rightful holder of the papacy. The conflict was political, rather than doctrinal, in nature.

In 1309, Pope Cloudless V, due to political considerations, moved to Avignon in southern France and exercised his pontificate there. For lx-9 years popes resided in Avignon rather than Rome. This was non simply an obvious source of confusion only of political animosity as the prestige and influence of the city of Rome waned without a resident pontiff. Though Pope Gregory XI, a Frenchman, returned to Rome in 1378, the strife between Italian and French factions intensified, especially following his subsequent death. In 1378 the conclave, elected an Italian from Naples, Pope Urban Half dozen; his intransigence in office soon alienated the French cardinals, who withdrew to a caucus of their own, asserting the previous election was invalid since its determination had been made nether the duress of a riotous mob. They elected ane of their own, Robert of Geneva, who took the name Pope Cloudless Vii. By 1379, he was back in the palace of popes in Avignon, while Urban 6 remained in Rome.

For most forty years, in that location were two papal curias and ii sets of cardinals, each electing a new pope for Rome or Avignon when death created a vacancy. Each pope lobbied for back up among kings and princes who played them off against each other, irresolute fidelity according to political reward. In 1409, a quango was convened at Pisa to resolve the issue. The Council of Pisa declared both existing popes to be schismatic (Gregory XII from Rome, Benedict XIII from Avignon) and appointed a new i, Alexander V. But the existing popes refused to resign and thus there were three papal claimants. Another council was convened in 1414, the Council of Constance. In March 1415 the Pisan pope, John XXIII, fled from Constance in disguise; he was brought back a prisoner and deposed in May. The Roman pope, Gregory XII, resigned voluntarily in July. The Avignon pope, Benedict XIII, refused to come to Constance; nor would he consider resignation. The council finally deposed him in July 1417. The council in Constance, having finally cleared the field of popes and antipopes, elected Pope Martin V equally pope in November.

Criticism of Church building corruption - John Wycliff and Jan Hus [edit]

John Wycliffe (or Wyclif) (1330–1384) was an English scholar best known for denouncing the corruptions of the Church, and his sponsoring the first translation of the Bible from Latin into English language. He was a precursor of the Protestant Reformation. He emphasized the supremacy of the Bible, and called for a directly relationship betwixt man and God, without interference by priests and bishops. Declared a heretic after his decease, his followers, called Lollards, faced persecution by the Church building of England. They went clandestine for over a century and played a role in the English language Reformation.[23] [24]

Jan Hus (or Huss) (1369?–1415) a Czech theologian in Prague, was influenced by Wycliffe and spoke out against the corruptions he saw in the Church building; his continued defiance led to his excommunication and condemnation by the Quango of Constance, which also condemned John Wycliff. Hus was executed in 1415, but his followers arose in open up rebellion. Betwixt 1420 and 1431, the followers of Hus, known equally Hussites, defeated v consecutive papal crusades. The wars ended in 1436 with the ratification of the compromise Compacts of Basel past the Church and the Hussites. Hus was a forerunner of the Protestant Reformation and his memory has become a powerful symbol of Czech culture in Bohemia.[25]

Italian Renaissance [edit]

Michelangelo'southward Pietà in St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican city

The Renaissance was a menstruation of slap-up cultural modify and accomplishment, marked in Italy by a classical orientation and an increase of wealth through mercantile merchandise. The city of Rome, the Papacy, and the Papal States were all affected past the Renaissance. On the one hand, it was a time of great artistic patronage and architectural magnificence, where the Church pardoned such artists as Michelangelo, Brunelleschi, Bramante, Raphael, Fra Angelico, Donatello, and Leonardo da Vinci. On the other mitt, wealthy Italian families oft secured episcopal offices, including the papacy, for their own members, some of whom were known for immorality, such equally Alexander Six and Sixtus Iv.

In addition to beingness the caput of the Church, the Pope became one of Italy's most of import secular rulers, and pontiffs such as Julius Two often waged campaigns to protect and expand their temporal domains. Furthermore, the popes, in a spirit of refined competition with other Italian lords, spent lavishly both on private luxuries but also on public works, repairing or building churches, bridges, and a magnificent organization of aqueducts in Rome that still function today. It was during this time that St. Peter's Basilica, maybe the most recognised Christian church, was built on the site of the onetime Constantinian basilica. Information technology was besides a time of increased contact with Greek culture, opening up new avenues of learning, particularly in the fields of philosophy, poetry, classics, rhetoric, and political science, fostering a spirit of humanism—all of which would influence the Church.

Fall of Constantinople (1453) [edit]

In 1453, Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire. Under Ottoman rule, the Greek Orthodox Church building acquired substantial power as an democratic millet. The ecumenical patriarch was the religious and administrative ruler of the unabridged "Greek Orthodox nation" (Ottoman administrative unit of measurement), which encompassed all the Eastern Orthodox subjects of the Empire.

As a result of the Ottoman conquest and the fall of Constantinople, the entire Orthodox communion of the Balkans and the Near Eastward became suddenly isolated from the Westward. For the next four hundred years, it would exist confined inside a hostile Islamic world, with which it had lilliputian in common religiously or culturally. This is, in part, due to this geographical and intellectual confinement that the voice of Eastern Orthodoxy was not heard during the Reformation in sixteenth-century Europe. As a result, this of import theological debate frequently seems strange and distorted to the Orthodox. They never took part in it and thus neither Reformation nor Counter-Reformation is part of their theological framework.

Religious rights under the Ottoman Empire [edit]

The new Ottoman government that arose from the ashes of Byzantine civilization was neither primitive nor barbaric. Islam not only recognized Jesus equally a smashing prophet, but tolerated Christians as some other People of the Volume. Equally such, the Church building was not extinguished nor was its canonical and hierarchical arrangement significantly disrupted. Its administration connected to part. One of the first things that Mehmet the Conqueror did was to permit the Church building to elect a new patriarch, Gennadius Scholarius. The Hagia Sophia and the Parthenon, which had been Christian churches for well-nigh a millennium were, admittedly, converted into mosques, yet countless other churches, both in Constantinople and elsewhere, remained in Christian hands. Moreover, information technology is hitting that the patriarch's and the hierarchy's position was considerably strengthened and their power increased. They were endowed with ceremonious as well equally ecclesiastical power over all Christians in Ottoman territories. Considering Islamic law makes no distinction between nationality and religion, all Christians, regardless of their linguistic communication or nationality, were considered a unmarried millet, or nation. The patriarch, as the highest ranking hierarch, was thus invested with civil and religious authorisation and made ethnarch, head of the entire Christian Orthodox population. Practically, this meant that all Orthodox Churches within Ottoman territory were nether the control of Constantinople. Thus, the say-so and jurisdictional frontiers of the patriarch were enormously enlarged.

However, these rights and privileges (see Dhimmitude), including freedom of worship and religious organisation, were often established in principle just seldom corresponded to reality. The legal privileges of the patriarch and the Church depended, in fact, on the whim and mercy of the Sultan and the Sublime Porte, while all Christians were viewed every bit little more than than second-class citizens. Moreover, Turkish corruption and brutality were non a myth. That information technology was the "infidel" Christian who experienced this more than than anyone else is non in doubt. Nor were pogroms of Christians in these centuries unknown (see Greco-Turkish relations).[26] [27] Devastating, too, for the Church was the fact that information technology could not bear witness to Christ. Missionary work amongst Moslems was dangerous and indeed impossible, whereas conversion to Islam was entirely legal and permissible. Converts to Islam who returned to Orthodoxy were put to expiry every bit apostates. No new churches could be congenital and even the ringing of church bells was prohibited. Education of the clergy and the Christian population either ceased altogether or was reduced to the about rudimentary elements.

Run into also [edit]

- History of Christian theology

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

- Christianization

- Timeline of Christianity

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Catholic–Protestant relations

Citations [edit]

- ^ Davies Europe pp. 291–293

- ^ Woollcombe, K.J. "The Ministry and the Gild of the Church in the Works of the Fathers" in The Historic Episcopate. Kenneth M. Carey (Ed.). Dacre Press (1954) p.31f

- ^ R. Gerberding and Jo Anne H. Moran Cruz, Medieval Worlds: An Introduction to European History 300–1492 (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2004), p. 33.

- ^ a b Alick Isaacs (14 June 2015). "Christianity and Islam: Jerusalem in the Eye Ages - 1. Jerusalem in Christianity". The Jewish Agency. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ^ Richards, Jeffrey. The Popes and the Papacy in the Early on Centre Ages 476–752 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979) p. 36

- ^ Joyce 1906, pp. 135–6.

- ^ On the development of penitential practice, run into McNeill & Gamer, Medieval Handbooks of Penance, (Columbia University Printing, 1938) pp. 9–54

- ^ Mayr-Harting, H. (1991). The coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania Country University Press.

- ^ Chaney, W. A. (1970). The cult of kingship in Anglo-Saxon England; the transition from paganism to Christianity. Manchester, Eng.: Manchester University Press.

- ^ a b Patrick J. Geary (2001). "Peasant Faith in Medieval Europe". Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie. Persée. 12: 185–209. doi:x.3406/asie.2001.1170.

- ^ Epitome, Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754

- ^ The Nifty Schism: The Estrangement of Eastern and Western Christendom

- ^ Ware, Kallistos (1995). The Orthodox Church building London . St. Vladimir's Seminary Printing. ISBN978-0-913836-58-three.

- ^ History of Russian Philosophy by Nikolai Lossky ISBN 978-0-8236-8074-0 Quoting Aleksey Khomyakov pg 87.

- ^ The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church building by Vladimir Lossky, SVS Printing, 1997. (ISBN 0-913836-31-i) James Clarke & Co Ltd, 1991. (ISBN 0-227-67919-9)

- ^ France, John. (1996). Victory in the Eastward : a armed services history of the Kickoff Crusade . Cambridge Univ. Printing. ISBN0-521-41969-7. OCLC 258294189.

- ^ Beaumont, A. A.; Atiya, Aziz Suryal (Apr 1939). "The Crusade in the Afterwards Eye Ages". The American Historical Review. 44 (3): 600. doi:ten.2307/1839922. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1839922.

- ^ For such an assay, see Brian Tierney and Sidney Painter, Western Europe in the Middle Ages 300–1475. 6th ed. (McGraw-Hill 1998)

- ^ Potato, C. (2012). God's Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern Earth. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ^ "From Eastern Roman to Byzantine: transformation of Roman culture (500-800)". Indiana University Northwest. Archived from the original on sixteen September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Sarieva, I. (1995). Some Problems of the Religious History of Bulgaria. Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe, 15(1).

- ^ cadre.ac.u.k.

- ^ G. R. Evans, John Wyclif: Myth & Reality (2006)

- ^ Shannon McSheffrey, Lollards of Coventry, 1486–1522 (2003)

- ^ Thomas A. Fudge, Jan Hus: Religious Reform and Social Revolution in Bohemia (2010)

- ^ The Australian Institute for Holocaust and Genocide Studies Archived vii June 2007 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times.

- ^ http://www.helleniccomserve.com/pdf/BlkBkPontusPrinceton.pdf[ bare URL PDF ]

References [edit]

- Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford, United kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN0-nineteen-520912-5.

Print resource [edit]

- González, Justo 50. (1984). The Story of Christianity: Vol. 1: The Early Church building to the Reformation . San Francisco: Harper. ISBN0-06-063315-8.

- Grabar, André (1968). Christian iconography, a study of its origins . Princeton University Press. ISBN0-691-01830-eight.

- Guericke, Heinrich Ernst; et al. (1857). A Manual of Church History: Ancient Church History Comprising the First Six Centuries. New York: Wiley and Halsted.

- Hastings, Adrian (1999). A World History of Christianity. 1000 Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN0-8028-4875-three.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1975). A History of Christianity, Book 1: Beginnings to 1500 (revised ed.). San Francisco: Harper. ISBN0-06-064952-vi. (paperback).

- Morris, Colin (1972). The discovery of the individual, 1050–1200. London: SPCK. ISBN0-281-02346-viii.

- Morris, Colin (1989). The papal monarchy : the western church from 1050 to 1250. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN0-19-826925-0.

- Morris, Colin (2006). The sepulchre of Christ and the medieval West : from the start to 1600. Oxford: Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0-xix-826928-ane.

- Shelley, Bruce L. (1996). Church History in Plain Linguistic communication (2nd ed.). ISBN0-8499-3861-9.

Online sources [edit]

- Joyce, Patrick Weston (1906). A smaller social history of aboriginal Ireland, treating of the government, armed services system, and law; religion, learning, and art; trades, industries, and commerce; manners, community, and domestic life, of the aboriginal Irish people (PDF) (An abbreviation of my larger piece of work, 'A social history of ancient Ireland' ed.). London ; New York : Longmans, Light-green, and Co. Retrieved 21 Oct 2016.

External links [edit]

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christianity_in_the_Middle_Ages

0 Response to "Before the Gregorian Reform the Latin Church at the Turn of the First Millennium Book Review"

إرسال تعليق